Pilots fly circling approaches when it’s not possible to do a straight-in approach to the runway after an instrument approach.

Circling approaches are necessary for a variety of reasons. The most common are strong tailwinds, obstacles, high descent angles and/or the final approach segment exceeds 30 degrees from the approach runway.

So, that’s the book answer. You’re here for the practical answer. Let me start with a simple example.

You’re on an ILS approach to runway 02 but the winds are out of the south at 15 knots. Only a fool would land with a 15-knot tailwind, so instead of landing on runway 02 you enter an extended left downwind and land on runway 18. That’s a circling approach!

You are simply aligning the aircraft with the best runway after you break out of the clouds on a normal instrument approach.

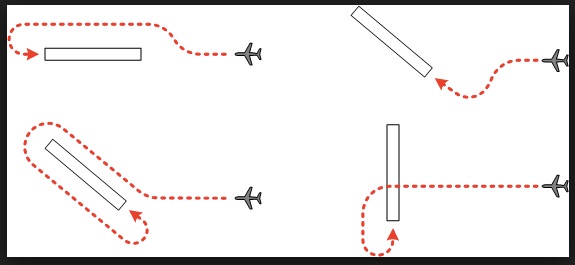

A picture is worth a thousand words:

There are a hundred different reasons and ways you can do a circling approach. Each scenario is different, but the fundamentals are the same: you need to get aligned with the best runway after you exit the clouds.

Note: this article will not go into the technical aspects of circling approaches. I pride myself on writing practical articles on difficult aviation topics. I left out the math on purpose. If you would like to know more, scroll to the very bottom where I provide two in-depth articles on how circling approaches are created.

But, if you just want to know how to fly them without crashing, read on.

What are circling approaches?

First, let me explain something, circling approaches aren’t “approaches” in the traditional sense. An ILS is a type of approach, a VOR is an approach and an RNAV is also a type of approach. A “circling” approach is a term used to describe the circling minima you will find on an ILS, RNAV, VOR, LOC, BC or GPS approach.

Circling approaches will always start in a normal approach (ie ILS, RNAV, VOR…) but it will terminate with a circle-to-land maneuver.

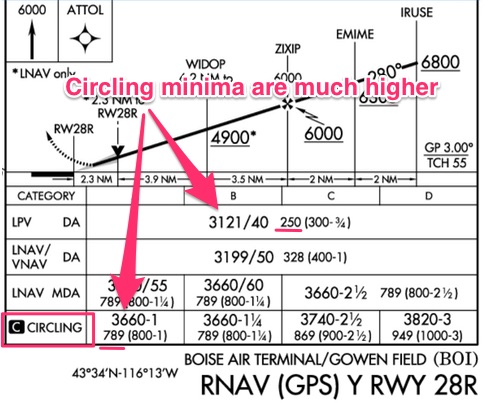

Circling approaches always have higher minimums than any other approach because the pilot must maintain visual contact with the runway throughout the entire maneuver. The higher minimums allow for a greater margin of safety.

Confusing? Here’s a picture of an RNAV approach with higher circling minimums:

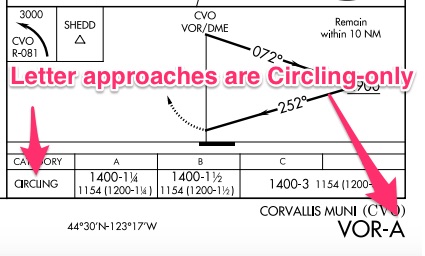

What are Circling-only approaches?

Circling-only approaches are rare, but you will run across them. You can easily spot them because they have a letter after the type of approach.

The example below is a VOR-A circling-only approach.

Circling-only approaches do not allow a straight in approach so you will only see circling minima.

Circling approaches are a last resort. You should choose a different approach whenever possible.

Sometimes, though, there aren’t any other options.

The Instrument Procedures Handbook explains the reasons for building circle to land only approaches:

- The final approach course alignment with the runway centerline exceeds 30°.

- The descent gradient is greater than 400 feet per nautical mile from the FAF to the threshold crossing height. When this maximum gradient is exceeded, the circling only approach procedure may be designed to meet the gradient criteria limits. This does not preclude a straight-in landing if a normal descent and landing can be made in accordance with the applicable CFRs.

- A runway is not clearly defined on the airfield.

How do you fly a Circling Approach?

This is like asking how to enter a traffic pattern. It depends on the situation.

Because each approach and airport are different, you will have to use your basic understanding of traffic pattern flying to figure out the best way to land.

Here are some examples again of how you could execute a circle-to-land approach:

The key is to plan your circling approach during cruise.

Never initiate a circle-to-land maneuver without having a plan on how you will land or do a missed approach.

You always have a plan when you fly VFR, right? The same concept applies for circling approaches.

General Rules on Circling Approaches

Frequency:

Pilots will do very few circling approaches in their career especially nowadays with more RNAV approaches. Most instrument airports have approaches to all runways.

Safety:

They are also dangerous when not properly planned and briefed. Successful circling approaches start at cruise with a thorough briefing and plan of action.

They are so dangerous, the airlines only permit circle to land approaches during VMC conditions and during the day.

This is what the FAA’s Instrument Procedures Handbook has to say about circling approaches. I included this quote because I urge you to treat circle-to-land approaches with the utmost of respect.

“Circling approaches are one of the most challenging flight maneuvers conducted in the NAS, especially for pilots of CAT C and CAT D turbine-powered, transport category airplanes. These maneuvers are conducted at low altitude, day and night, and often with precipitation present affecting visibility, depth perception, and the ability to adequately assess the descent profile to the landing runway.“ FAA IPH page 4-8

Responsibilities of the pilot:

Once a pilot is on a circling approach they are responsible for seeing and avoiding obstacles and clouds.

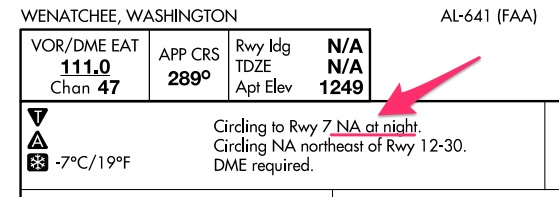

Restrictions:

Some airports will not allow a circle to land approaches in some circumstances. Always check the notes on the approach chart.

Advice:

Never do circling approaches at night to an unfamiliar airport.

Technique:

If you are single pilot do left-hand traffic patterns so you can always keep the airport in sight.

Recent changes to circle-to-land approaches:

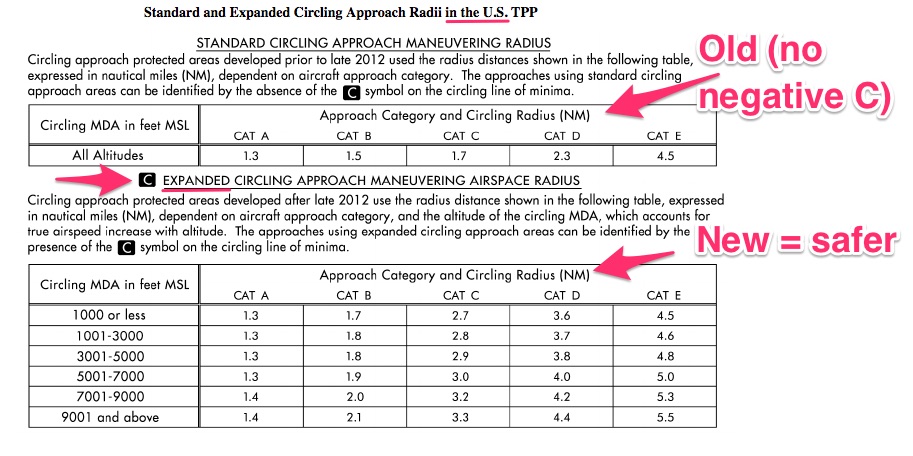

In order to increase the safety of circling approaches, the FAA has increased the circling radius of these approaches. They found the old TERPs didn’t account for true airspeed at higher altitudes, more realistic bank angles, and strong winds.

As a result, the radii increase. Here is a chart with the old and new radius. Be careful when flying the charts without the new “C” symbol as you may not be able to do a safe circle-to-land approach especially in larger aircraft.

How do you do a missed approach procedure on a circle-to-land approach?

I know why you’re asking this: because you are about to take a check ride and someone is going to ask you about it.

Also, in real world flying this question is completely irrelevant because smart pilots would never get themselves in this position.

Before I answer the question, I’m going to yell at you in all caps:

YOU SHOULD NEVER GET YOURSELF INTO A POSITION TO DO A MISSED APPROACH ON A CIRCLE-TO-LAND APPROACH!

To further emphasize this point, check out what the AIM says in general about circling approaches:

“Circling may require maneuvers at low altitude, at low airspeed, and in marginal weather conditions. Pilots must use sound judgment, have an in-depth knowledge of their capabilities, and fully understand the aircraft performance to determine the exact circling maneuver since weather, unique airport design, and the aircraft position, altitude, and airspeed must all be considered.” AIM 5-4-20 (f)

Okay, but how do you do a circling missed approach if you were a fool?

Missed approaches on circling to lands are complicated and it will depend on a variety of factors to include ATC contact, radar coverage, VOR location, and terrain.

This is why making a plan in cruise is essential to safely execute a circling missed approach. In cruise, you will have had time to digest the weather report and figured out if the circling minimums were close to the cloud bases.

If the cloud bases are close to the circling minimums you need to plan then visualize exactly how you will execute the missed approach during every part of the circle-to-land maneuver.

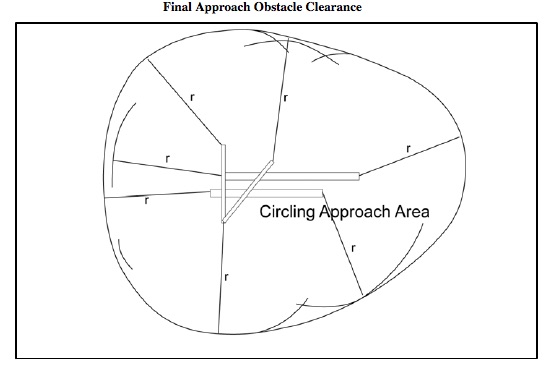

Each circling missed is unique, but one thing is for sure: you must stay within the protected zone!

The easiest way to do that is to turn towards the center of the airport and climb over the airport. which may be very difficult to do in IMC with no glass cockpit.

This is what the Instrument Procedure’s Handbook says:

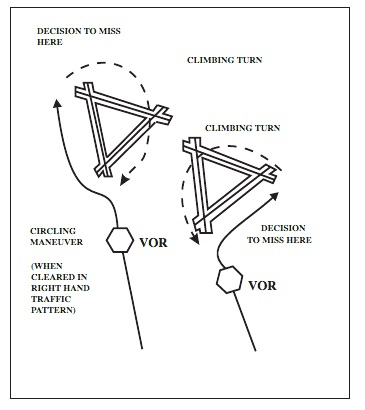

“To become established on the prescribed missed approach course, the pilot should make an initial climbing turn toward the landing runway and continue the turn until established on the missed approach course. Inasmuch as the circling maneuver may be accomplished in more than one direction, different patterns will be required to become established on the prescribed missed approach course, depending on the aircraft position at the time visual reference is lost.”

The AIM reminds pilots that doing a missed approach once you initial the maneuver and exit the circling area will not guarantee you obstacle clearance.

Below is a picture of a couple fo possible scenarios published in the AIM. But take it with a grain of salt because these are only two examples and doesn’t apply to all airports. What if the VOR is nowhere near the airport?

I’m going to say it again: figure out your plan in cruise before you initiate the approach and brief it in depth with your co-pilot. I can’t cover all the scenarios in this article.

Also, remember missed approach procedures assume a 200 ft/NM climb rate unless published otherwise. This may be difficult at high altitude on a hot day with a small aircraft or if you lose an engine.

Additional Reading:

Comparing old and new TERPS (note: there is a lot of math in this article, but it’s a great article)

Code 7700’s in-depth article on circling approaches (with lots of math!)

Aeronautical Information Manual: Missed Approach Procedures (this is a great review)

Instrument Procedures Handbook by the FAA (every IFR pilot should read this cover to cover)